March 17, 2022

Published by admin

If you have pitch problems when singing it can feel like the worst thing ever. It’s embarrassing and makes you never want to sing, which is a problem if you enjoy singing and also want to sound good while singing. Fortunately for us there are many different exercises you can do to improve your pitch while singing. They’re all fairly accessible and are things that, if we practice them regularly, will help us tremendously in improving our pitch while singing.

The weirdest thing about this problem is that you can often tell once you sing that you’re off pitch, and you know you aren’t singing the correct pitches. You just don’t know how to sing the correct ones and can’t hear the correct ones right away. But you know that what comes out of your voice isn’t correct. It’s a strange problem to have because you know it’s wrong, but it’s almost like playing the piano and guessing where the notes are without knowing what they’ll sound like. You’re guessing at what keys you’re playing and you know you’ve played the wrong keys once you play them, but you just can’t seem to find where the right keys are.

The problem is often with the connection between your ears and your voice. You need to know how to set up your vocal cords to sing the pitches you’re hearing before you sing them. That’s the connection you need.

Strap in because this is going to be quite a lengthy post.

Here’s a quick background story about myself.

I used to have pitch problems. I had pitch problems in high school and even for a little bit at Berklee College of Music. I knew I had these problems but I wasn’t sure what to do about them. I still remember in high school taking the AP exam for Music Theory and just hating the sight singing portion. It was absolutely brutal because I couldn’t hear the pitches in my head and what came out just sounded terrible, and I knew it. I could also tell from the face of my proctor that it didn’t sound good to them either. It was mortifying. But I enjoyed music too much to let that make me quit, so I kept playing guitar and practicing singing on my own and I eventually got to Berklee.

There I took ear training classes and practiced singing on my own in my room, but I never wanted anyone to hear me sing because I was so self conscious about it. I’d recorded myself singing a number of times and I knew that I didn’t sound how I wanted to sound. Singing with the piano helped a lot. I could guide myself with the melody, and eventually once I knew the melody well enough I didn’t need to play the melody on the piano. That gave me some extra confidence.

At Berklee I had my first two semesters of ear training with Cercie Miller. I loved having Cercie Miller as a teacher. She made ear training super fun and enjoyable and always related the exercises and material back to real world music. She was also really supportive of the students and encouraged us a lot. Her classes also helped me sing on pitch better not just because having a tool like solfege helped me a lot, but because she had us perform lots of vocal exercises and solfege ear training exercises that helped me better connect my voice to my inner ear.

I did well in her classes, but she kept me after one of my last ear training exams to talk to me. The exams were done individually and she knew I wouldn’t have her the next semester for ear training, so she pulled me aside to talk to me about my pitch problems.

Cercie told me that she’d noticed I had pitch problems and she asked who my next ear training teacher would be. I told her I was going to have Robin Ginenthal for my next ear training class. She said Robin would be a good next teacher because Robin was a singer; Cercie played saxophone. And Cercie told me that having Robin as a teacher would be perfect because she’d be better able to guide me in improving my singing pitch and helping me fix my pitch problems. But there was a caveat. Cercie told me that because she mentioned this to me, and she knew I was well aware of it, I needed to tell Robin within one of the first classes because then Robin would be able to help. She told me that me taking responsibility, being proactive about fixing it, and asking for help will let Robin know that I’m serious about doing well in her ear training class.

So I told her.

We’ll get to that in a minute, but something to remember was that during this whole time I was also practicing singing exercises on my own almost every day. I enjoyed them and I knew they’d help me feel more comfortable while singing. I found some videos by the singer Eric Arceneaux. I watched a bunch of his videos and practiced many of the exercises he recommended. I regularly practiced vocal exercises, scales, and breathing exercises because I figured it was all connected to making me feel more comfortable as a singer.

If you’d like vocal exercises specifically about improving your vocal tone and vocal skills I highly recommend you watch his videos. Some of the old ones that I watched all those years ago in high school are still useful today. His videos are an incredible resource.

Back to the original story.

During one of my first classes with Robin I talked to her after class and told her I had pitch problems, and I told her the whole story; I had Cercie Miller and she told me that she (Robin) would be able to help me correct those problems. And I was all about it too. I was so excited to have something that’d help me be a better singer because I enjoyed singing and I wanted to be able to sing well. I just never had vocal lessons and that wasn’t a part of my curriculum at Berklee. But I wanted any help I could get. Robin told me to see her at her office hour. And she gave me a ton of exercises to help me.

And I practiced them regularly. Basically every day I’d do at least one of the exercises. Eventually you can do them by yourself and won’t need an instrument, but an instrument is definitely needed at first. Once I was able to do them by myself I’d often walk around Boston practicing ear training exercises. They also helped me so much that I felt comfortable joining a church choir across the street from Berklee and sight singing some of the songs in the church service. I mention that to say that they work … really well.

So let’s get into what those exercises were.

Table of contents

1. Sit up straight

2. Random pitch matching

– How do I know if I’m hitting the correct note?

– Practice methodology

3. Pitch matching within a scale

4. Sing scales in solfege

5. Sing the major triad

6. Sing the minor triad

7. Tendency tones

8. Random scale degrees and drone do

9. Random chromatic scale degrees and drone do

10. Don’t drone do

Additional exercises

Final notes

1. Sit up straight

The first thing I suggest before practicing any vocal exercise is to sit up straight. This allows you to get better air flow and breathe a little better. It also helps you have more control over your air supply and your voice. You’ll better control your voice sitting up straight.

The next thing would be to breathe with your diaphragm. That means you’re breathing with your stomach. You should feel your stomach rising and falling as you inhale and exhale. This is how singers breathe for more power and control and will help you be more comfortable and more in control of your pitch while singing. This isn’t necessarily a “pitch” exercise, but it’s something that’ll help you feel more confident and more in control of your own voice.

2. Random pitch matching

This one is fairly straight forward. Choose random notes and pitch match them. I used a random number generator to do this when I originally started doing it. The goal is to play a note on your instrument, and match that pitch with your voice. That’s it.

But there are a few other things we can do here to improve our pitch matching skills.

The main thing you want to do is to hear the pitch in your head. This will make the exercise go a little slower, but it will help in making it easier in the long run. Put in a little extra time now to make things easier in the future. So you’d choose a note, play the note on your instrument, hear it in your head, sing it, and then double check by singing with the instrument.

The reason you want to hear the pitches in your head before you sing them is to improve the connection between the audiated sound in your head and how you’ll have to place your vocal cords to make that sound. Try to hear it as accurately and loudly as you can. Make that inner note sound incredibly accurate and detailed. This is also something that professional singers do to ensure that they’re hitting the correct notes. One thing I tell my students is, “if you can’t hear it, you can’t sing it.” You need to be able to hear it first before you sing it.

One thing you want to avoid when doing this is sliding into the note. Often people with pitch problems when singing will slide up to the note, but we don’t want to do this. This can cause other problems later where you end up getting into the habit of always sliding into every note you sing and that’s not always the sound you want. So we want to avoid that habit from the beginning. The alternative is a little more difficult, exposes your pitch problems a little more, and that’s simply hitting the note right away. To do this you’ll need to hear it in your head more accurately and know how to place your vocal cords before you sing the note.

An example of professional singers doing this is Mariah Carey. When performing live she’ll often put her finger to one of her ears and plug that ear up a little. This allows her to better hear her own voice a little better. Singers do this to better tune their own voice especially when singing complicated vocal runs or when singing in high registers.

How do I know if I’m hitting the correct note?

There are a few ways to tell if you’re singing the correct note. The first way is to simply use your ears. I know this one isn’t super helpful, but the notes should sound and feel consonant. If it sounds and feels “bad” or like the notes are rubbing together too much and clashing, you’re likely not singing the same note.

Another way to tell is to feel your face. Often when singing the correct note, especially with an acoustic instrument like guitar or piano, that’s also playing that note, you can feel it in your face. You should feel a very distinct vibration in the front of your face when you’re hitting the same note. This is mostly useful when you’re playing an instrument at the same time, so it’s helpful to be able to play an instrument like piano or guitar here.

You can also listen for “wavering” in the note. When you’re singing the exact same note as an instrument there shouldn’t be any wavering. If you’re singing “almost” the correct pitch you’ll hear a whole lot of fast wavering. If you’re singing a harmony like a fifth or a third there will be gentle and fairly pleasant wavering. You can hear this when tuning two guitar strings together. When they’re not the exact same notes there will be a lot of fast wavering, but once they’re the same pitch there won’t be a whole lot of wavering.

You could also record yourself pitch matching if this is especially hard and you’re especially concerned, though I think the above two steps should be used first. Another option, if you have the resources, is to hire a vocal coach. In that case feel free to send me a message.

Practice methodology

We’ll be talking about a few different ways to practice these exercises, and I’ll describe each practice method within the different sections. But the main idea is that if you can hear that two pitches are different, and when you sing them you sing generally in the correct direction, you can learn to sing on pitch. This means if you play two pitches, one higher and one lower, and when you try to sing them you sing two pitches, one higher and one lower, you’ll be able to tune your voice correctly.

The problem is mainly the connection between your ears and your vocal cords. That’s the connection you need to strengthen. Singing a note doesn’t just mean that you let it out and it comes out. In order to sing a pitch accurately you need to be able to hear that pitch in your head and know how to form your vocal cords to create that pitch. This means there are two main places where the problem can occur; in our head and when we go to form our vocal cords to create a pitch. In order to strengthen it you need to improve your inner hearing as well as your vocal skills.

So these are all things that we can work on with the assistance of an instrument.

The goal is to use the instrument to guide us at first. This helps us develop our own internal sense of pitch using the instrument’s pitches as guides. After that has been somewhat established we can strengthen that sense of pitch by taking some of that assistance away. This fores us to rely on our own sense of pitch just a little bit more, and we can use the instrument to double check our pitch. This reinforces the internal sense of pitch that we’re developing as well as forcing us to start relying on that to sing.

Then we slowly remove the assistance so that we’re mostly relying on our own internal pitch. The better you get at performing these exercises the more you’ll notice that you may not need the instrument for assistance. I suggest doing this intentionally because if a specific student is shy about singing, they may always want to have that instrument there. So if you build it into the exercises you practice you don’t run as much of a risk as becoming reliant on the instrument. Eventually the goal is to remove the assistance so much that we don’t even need it anymore. At this point your pitch problems will be completely gone and you’ll have some killer ears and some killer vocal pitch.

3. Pitch matching within a scale

After you’ve practiced pitch matching randomly, the next step is to pitch match within a scale. I put this one next because this is where we start to practice hearing different scale degrees. At first though, randomly pitch matching simply helps you develop a connection between the notes in your head and the feelings in your vocal cords.

Choose a scale; I’d start with a major scale. And choose notes from that scale randomly to pitch match. This will mean more notes are repeated than before, but that’s okay. We just want to get the feeling of singing within one scale. You can choose any other scales you know here, but make sure that you go through all of the different keys and different areas of your vocal range. You want to practice in as many keys as you can and do that all over your vocal range.

We still want to follow the above step of playing the note on the instrument, hearing the note in your head, and then singing it. We still want to strengthen the connection between the notes in our head and the notes that come out from our voice. It can help to hear the note sung in your head.

When I practiced this I used a random number generator set to give me a number from 1 to 7, and I would choose the octave for that note.

4. Sing scales in solfege

After you’ve gotten a solid handle on pitch matching the next step is to learn to sing scales in solfege. I know not everyone likes using solfege, but I’m a big fan. I’ve got a YouTube video on learning solfege that explains the basics of it that I suggest you check out.

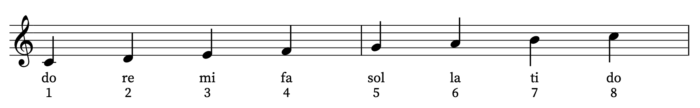

Solfege is an Italian naming system for scale degrees. For this step to be useful you don’t have to use solfege. You could use numbers. I just prefer solfege because there are different syllables for each scale degree and they’re only one syllable long. For a major scale, scale degree numbers and solfege both work well. These are both shown below.

These syllables are pronounced as in the words “dough”, “ray”, “me”, “fah”, “soul”, “lah”, “tea”, and “dough.”

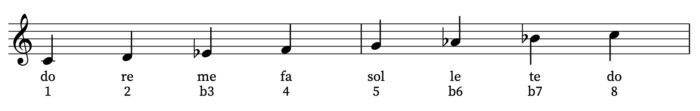

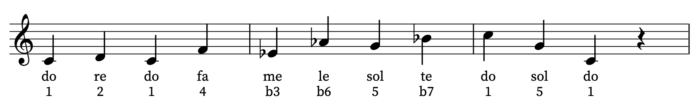

But with a minor scale it gets a little more complicated. Solfege still has only one syllable per scale degree, but scale degree numbers have multiple syllables for the altered scale degrees. “Flat three”, “flat six”, and “flat seven” are a lot more to sing than “me”, “le”, and “te.” These syllables are pronounced as “may”, “lay”, and “tay.” This is pictured below.

For a start I suggest you just learn the major and minor scale syllables, and sing an octave of those in different keys. That way you’re practicing hearing the scale degrees and the relationships between them in different keys, and working on remembering those solfege syllables.

The end goal here is to be able to sing these scales without needing an instrument, but at the beginning you want to use the same process as pitch matching; play the note, hear it in your head, sing it, and double check with the instrument. This gets you to hear the sound of the pitch in your head first before you sing it so you can improve your own internal sense of pitch and again strengthen the connection between your internal auditory notes and your vocal cords.

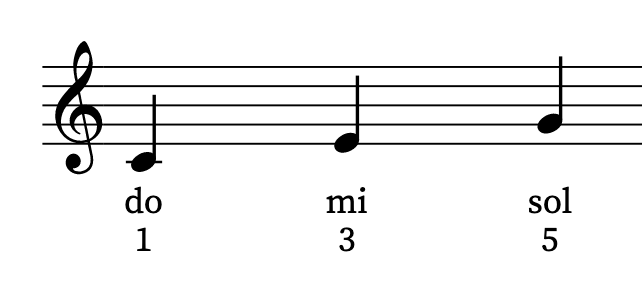

5. Sing the major triad

Next we’ll sing the major triad. This is pictured below.

Again the goal is to practice singing this in different keys all over your vocal range. At first I suggest you again use the same process as pitch matching; play it, hear it, sing it, and double check. And practice this in a different order than just up and down. Start from mi and sing sol–do. Start from mi and sing do–sol. Start from the octave above of do and sing down a full octave of the triad.

Any variations you can think of will help you internalize the sound even better and get your voice more used to singing common vocal patterns.

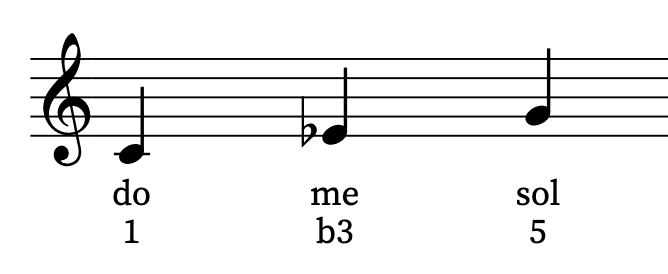

6. Sing the minor triad

Next sing the minor triad. This is pictured below.

Use the same process as above. Sing in all different keys and all over your range. Double some notes and sing the degrees in different orders.

The goal of these two exercises is to get your ears tuned to

7. Tendency tones

Tendency tones are scale degrees and where they tend to resolve to. They’re the same in both the minor and major scale, which I’ve pictured below.

Robin Ginenthal would start almost every class by having us do some basic vocal warm ups, and then doing this exercise, and it helped so much in hearing different melodies in solfege. Going over and repeating each of these so many times helps you remember and recognize each of these resolutions. It’s especially useful because so many melodies resolve in these ways.

To start use the same method we’ve been using to practice our pitch skills; play it, hear it, sing it, and double check. Eventually this will be easy to hear because you’ll know what each different resolution sounds like. Once you think you have a better grasp of what this is supposed to sound like and your pitch when singing these tendency tones improves start to hear it in your head first. Give yourself do, then sing the next tendency tone by hearing it in your head, singing it, and double checking it. Don’t play it first. You want to start to rely on just your ears. So the process now is hear it, sing it, and double check.

What you’re hearing here is where each note wants to resolve to. In the major and minor scales certain scale degrees sound resolved and others sound unresolved. The notes of the root note triad all sound fairly resolved and all of the other notes don’t sound as resolved. So each one of these notes is resolving to a part of the triad.

My favorite part about this exercise is that it pays off quite quickly. It’s easier to hear than a lot of other exercises because it follows the patterns of music. When I started singing this for my ear training classes I started quickly hearing these resolutions in songs, which strengthens you ear even more. So not only does it improve your pitch while singing, it also improves your ear and your scale degree recognition when listening to a song.

8. Random scale degrees and drone do

This is one of the exercises that helped me the most in overcoming my pitch problems, and improving my vocal pitch. It’s an exercise I’d never thought to do, or never heard anyone describe until Robin Ginenthal taught it to me.

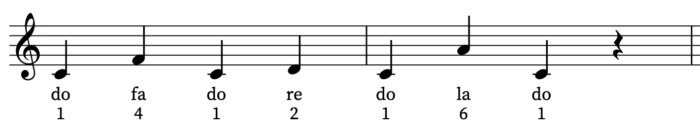

The idea is that you sing random scale degrees and then sing do. For example you may sing do, fa, do, re, do, la, and do.

For each of these you want to change the singing process a little bit. You want to give yourself do, and that’s it at first. Hear do, sing do, and double check with an instrument. After that choose a random scale degree, hear it, sing it, and then double check with your instrument. Then sing do again.

You want to root yourself with the root note of the scale. Keep that in your head, so you can orient yourself to the correct next scale degree. It helps to hear the notes in comparison to each other because then you can tune that interval.

This exercise is difficult and takes time to get all of the scale degrees in tune, but with dedicated practice it gets easier. It also helps if you can associate each interval leap with part of a song that you know well. That way you can use that song as a reference in your head for where each scale degree is.

I put this after the tendency tones because knowing your tendency tones will help a lot with this exercise. Being able to identify which tendency tone you’re singing helps. If at first you accidentally get fa and la confused, you can use your knowledge of tendency tones to help you. Fa resolves down a half step to mi, while la resolves down a whole step to sol. Keeping that in mind can help a lot.

The way I practiced this was with a random number generator. I’d set it to be out of 7 or 8 and I’d sing whatever scale degree number it gave me. If it gave me a 3 I’d sing mi. If it gave me a 6, I’d sing la, and so on.

9. Random chromatic scale degrees and drone do

Once you’ve got a good grasp of singing different scale degrees within both major and minor scales, it’s time to mix them together. After practicing all of the modes this will be a pretty natural progression, but I put it as an extra step because you’re not limiting yourself to one scale.

The way I practiced this was with a number generator. I’d set it to be out of 11 or 12 and sing whatever scale degrees it gave me. For this it’d be whatever pitch is that number of semitones away from do. If the number was a 3, I’d sing me. If it gave me a 7, I’d sing sol. If the number was an 8, I’d sing le. This does take a little counting at first, but it’s easier once you remember a few key intervals like 4, mi, and 7, sol. After that you can compare other numbers to those scale degrees.

This is definitely a little bit more difficult than the above step, but it helps a lot in improving your internal sense of hearing. In many ways this may improve it past someone who didn’t have pitch problems because you’re specifically focusing on something they haven’t thought to work on.

In addition to all of the pitch benefits, it also helps with being able to sight reading music. You’ll notice the last few steps help with other skills than simply singing on pitch. They help with general ear training a whole lot too. That’s because general ear training, in a lot of ways, goes together with singing on pitch. It’s all related because they both have to do with your internal sense of pitch. Improving that and improving your connection with your vocal cords will help.

10. Don’t drone do

The next progression after doing all of these is to do the last two exercises without droning do on your instrument. Start by doing the previous exercises without playing do, but still singing do. Once it’s easier with just singing do, start by just hearing do in your head. That was the hardest one for me at first. It gets easier the more you do it because you start to have a better sense of each scale degree by itself, and you internalize the root note more.

I suggest practicing this with a random number generator, just like the above two exercises, but don’t sing do every time you do it. Just sing the scale degrees.

This can be especially difficult with chromatic notes because you’re not comparing them to a home note or hearing them in relation to a scale as much anymore. But the extra effort that you need to put in in order to perform this exercise is well worth it.

Additional exercises

This next one gets a little complicated and a little involved. Sing the different diatonic arpeggios using solfege. I’ve included an image of this in C major below.

There might not be as many keys that you can perform this exercise in because it requires a larger vocal range than just one octave, but try to perform it in as many keys as you can. If you have to sing some of these arpeggios an octave down, that’s fine too. That should help with being able to sing more different keys.

If you’ve practiced these exercises a solid amount they should start to feel a little easier. For this one, the goal is the same as the above exercises; sing it by yourself without an instrument. But to get there we need to use the assistance of an instrument. So you can do both practice methods with this one. First start by playing each pitch, hearing it, singing it, and double checking it. Then once that’s comfortable practice just by playing do, hearing the next note, singing it, and double checking. And then slowly take away the assistance from the instrument where you’re just singing each arpeggio by itself, and only giving yourself notes that are really tricky for you.

Other exercises that help are more standard vocal exercises like singing five note scales and one octave arpeggios all throughout your range. These are a little more straight forward and don’t require solfege, but they get you used to singing different pitches and placing your vocal cords in the correct place. They can especially help if you practice different vowel sounds. They aren’t specifically for developing better pitch, but they’ll help you feel more comfortable as a singer, which will likely help you have better pitch while singing.

Final notes

Having pitch problems when singing can be incredibly frustrating both as a teacher and as a student, and I’ve been both. As a student it’s embarrassing and makes you never want to sing in front of an audience. It can also discourage you from even trying to sing because it can be a lot of extra work just to sound decent, but that work is definitely worth it. I sing all the time now, and I’ve directed choirs and musical theatre students. On a less serious note I love doing karaoke and still sing in my car as much as I used to, but now I sound a whole lot better doing it. No one would even know that I had pitch problems. I’ve even been described as a “good singer” by a lot of my co-workers.

So don’t be discouraged. Singing is incredibly enjoyable and satisfying once you’re comfortable with it and I recommend everyone learn how to sing enough to be comfortable.

Just keep practicing and keep working on it.

To give you an idea of how well these exercises work I currently teach music at a school and direct the students in singing many songs, as well as putting together a concert every winter. During that concert one of my students was singing a solo. He got nervous and sang the entire song in the wrong key. I restarted the song a few times to try to help him out, and eventually ended up singing the song with him … except I sang in the correct key and he sang somewhere between a half step and a whole step lower than me. That’s something I never would’ve thought I would’ve been able to do. I bring that up just to say how much these exercises work. They’ve improved my internal sense of pitch so much that I was able to hold my own while singing along with someone singing a very dissonant harmony.

They work incredibly well. I wish I’d known about some of these exercises earlier because they would’ve helped me be so much less anxious about singing when I had too.

I hope this post was useful and that it gave you some techniques on overcoming pitch problems.

ISJ

…