July 18, 2021

Published by admin

This post is specific to my fellow guitar players.

Strumming is something that can be a little tricky for guitar players. I recently taught a ukulele class and taught them a strumming pattern that I think often tricks people up.

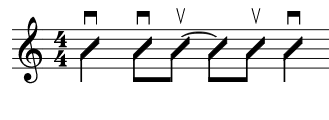

Here’s the rhythm:

And the way you’d strum this pattern is below:

The main thing that tricks people up about this rhythm is beat 3. You’er playing two up strums after each other, which means in order to strum it correctly, you have to strum down without actually hitting the strings. One of my students calls this a “ghost strum.” I like that name and have been using with other students ever since. You’re “strumming” but not hitting the strings, which mostly only feels weird, at first, for down strums.

Goals of strumming

The goal of strumming is to keep your hand moving at one speed the whole time. Your hand never stops moving while you’re strumming. It’s mostly a constant “down – up – down – up” pattern that continues for the entire strumming pattern.

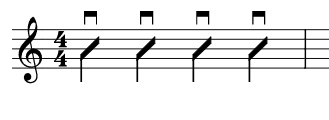

And if you’re playing only down strums like below:

In this strumming pattern you’re basically doing a “ghost strum” in between all of these notes. If you strum this pattern you’ll automatically “strum” up or do the motion for strumming up without hitting the strings.

The main reason we want to keep our hand moving while strumming is to keep a constant and even rhythm. Constant and even motions are more likely to create an even and constant tempo than uneven and intermittent movements. This is the primary reason that people do this.

Another reason people strum this way is because it’s idiomatic to the instrument. When you’re hearing someone strumming the guitar, you’ll likely hear someone strumming the down beats, or strong beats, as down strums and the weaker beats, or up beats, as up strums. You might sometimes here stuff broken up different where the 16th notes are up strums and the numbered beats (1, 2, 3, and 4) and the up beats (the ‘and’s) are down strums. But it’s the same idea. The weakest subdivision of the beat is the up strum.

The first pattern always tricks people up because you’re doing the same thing for an up strum.

How to practice this

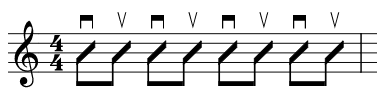

My first recommendation, whenever you come across a strumming pattern that’s similar to this that tricks you up is to first take it slowly. Practice incredibly slowly. Practice so slowly that each of the strums, both up and down, can be consciously focused on. Focus on each specific up and down strum and make sure that you are constantly doing an eighth note “down – up” pattern. Almost all 8th note strumming should feel relatively like this:

This pattern is how most strumming should feel. What this does is keep the momentum going. It keeps your hand moving at a constant pace, which helps you keep the tempo. If you’re doing uneven movements it’s harder to keep the rhythm even. Especially as a beginner, without much rhythmic practice, it’s important to keep this motion even and ongoing.

So whatever rhythm you’re strumming, if it’s eighth notes, try to make it feel like the above rhythm.

Remove the ties at first

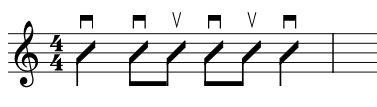

Another thing you can do to make this rhythm easier to play, when you practice at least, is to remove the ties.

Play this:

This way you’re literally playing that down strum that’ll become a “ghost strum.” Eventually you’ll want to remove this down strum, but this rhythm will get you acquianted with how that specific strum feels. So when you remove it you’ll be able to add in that “ghost strum” more easily because you’ll know how it feels.

And this technique can be used for any rhythm that has a similar tie. Practice it, at least at first, without the ties to get used to a simpler rhythm that is quite similar, and then add the ties back to be able to play the actual rhythm that you’d want to be able to play.

Practice combinations

After you’ve gotten comfortable strumming a few different strumming patterns start making them up yourself and practicing them. Add ties into different beats and see how easy that is to strum. Use only 8th notes and 8th note rests. Create different strumming patterns by yourself and practice as many different combinations as you can to get comfortable playing whatever strumming patterns you’ll see in music.

The more combinations of strumming patterns you practice, the more comfortable you’ll be playing different strumming patterns you come across in music.

ISJ

…

July 17, 2021

Published by admin

One of my students the other day asked me this question so I figured I’d make a post about it. I made a video a while ago about some of these so go check that out as well.

“How do I improve my sight reading?”

Here’s a list of 10 tips I’ve got:

- Do it a lot

- Look ahead

- Look for patterns

- Look through the piece

- Read lines

- Get better at recognizing chords

- Get better at recognizing scales

- Get better at recognizing rhythms

- Practice hymns or chorals on piano

- Practice Real Book tunes on guitar

Let’s start from the top

1. Do it a lot

This my biggest piece of advice and I know it’s not a fun answer. The main thing that has helped my sight reading has been doing it a lot and learning more music. Learning and playing and performing a ton of music has been the biggest thing that’s helped me improve my sight reading. I’ve music directed nine different musicals on piano, over the course of three years, and that alone has massively improved my sight reading. Each musical is about an hour and a half to two hours of music. That’s a ton of music.

If you really want to improve your reading, practice reading a lot. Take a piece of music every single day and play through it a few times. I’d recommend five times. Choose a piece that you’ll be able to play well the fifth or sixth time reading it through. That way you get enough practice with the piece to internalize some of the patterns, but you don’t have to spend much time practicing it to get it under your fingers. It also means that the piece is easy enough technique wise that you can physically play it easily, but the reading is the main thing that you’re practicing, which is what we want.

2. Look ahead

Imagine you’re reading a book outloud. When you do that do you look at the exact word that you’re saying as you’re reading it? Or are you looking slightly ahead?

And if you are looking directly at the exact word that you’re speaking, does it help you read a little more fluidly and easily if you do look ahead?

I’d bet it does.

That’s what you want to do with music. Look ahead a little bit. Try to look at the next beat, or the next few beats, or the next measure or next few measures. It’ll give you time to prepare to play them and to get your fingers in the right places to play those notes. You won’t have to identify the notes, dynamics, and articulations you have to play as you play them. You’ll identify them first, then play them later.

One way to practice this is with a partner. Have them hold up a piece of paper and cover up the beat that you’re playing as you go. Have them continue doing this throughout the entirety of the piece. They’re slowly moving this piece of paper across the music and covering up more and more music.

You could also practice this simply by trying to look ahead, though if this is something you struggle with it can be difficult at first. I recommend using a piece that is incredibly easy to play. Choose a piece you’ve played before. That way you can practice looking ahead at the music much more easily because you’ll be familiar with the finger patterns and note patterns. Or choose a piece that is very easily sight readable.

I notice that when I’m reading pieces that are easy to sight read I do this automatically. I’ve also practiced it a lot, but it becomes so much easier to do this when the piece itself is easy.

Try to look ahead at the next few measures at first, then try looking ahead at the rest of the page. That’s my favorite way to practice it; look ahead at the entire page as you’re playing it. It can help a lot and it’s a great way to get acquainted with looking at something that you aren’t playing yet.

3. Look for patterns

This one is broad so I’m going to look at specific patterns in other steps.

Look for patterns. Whatever patterns you can recognize. Look for scales, chords, intervals, and rhythms that you’ve seen before. One thing on piano that can help a lot is being able to recognize octaves and fifths in both hands. Being able to see them right away and recognize that two specific notes are an octave apart or a fifth apart is tremendously helpful because so much piano music has fifths and octaves. This same idea can be used for different intervals as well. Thirds and sixths are also fairly common intervals that occur in music and being able to recognize them easily will help you better sight read that piece of music.

We’ll talk about chords in another step, but whole chord progressions can be recognized after a good amount of musical performance and practice and sight reading. When I played through Grease for the first time that’s the main thing I did. I saw whole chord progressions and thought, “Oh okay cool this is a I – vi – ii – V chord progression.” Or other chord progressions I’ll recognize quickly, especially common ones. I – V – vi – IV is another common chord progression that would be useful to be able to recognize in all 12 keys. Same thing with ii – V – I. All of them are great to be able to recognize quickly, especially in all 12 keys.

Some of these patterns will become easier to recognize the more music you play, but if you can practice them ahead of time as well, and notice them when you play music you’ll be better off when you sight read.

4. Look through the piece

This one is incredibly simple. So simple it might seem unnecessary but it’s most definitely necessary.

Look through the piece and notice things. Look at the time signature. Look at the key signature. Look at any changes in those things. Look at the form of the piece. Look at the textures that are used. Look at any thematic materials.

Form is one thing that really helps me when I’m sight reading. I try to notice and get a general mental map of the form so that when I hit a repeated section I’m not surprised and I’m aware that it’s repeated material. That way I know that I’ve played it before and that I’ll be able to play it a little more easily the second time.

This step can take anywhere from 5 to 10 minutes depending on how long the piece is, but you’re looking to notice everything in the music not analyze it. Notice dynamics and articulations and tempos. Notice as much as you can. Notice which parts will be easy to play or which parts will be difficult to play. That last step can save you a lot of anxiety and stress when sight reading because you’ll be a little bit more prepared than had you not checked out the piece in this way.

I had a teacher at Berklee who would have us do this when studying scores. We’d literally sit in a room and go through the piece and he’d ask us, “What do you see?” The answers he wanted, which at the time confused us a bit, were things like, “I see quarter notes and staccatos and tenutos”, or “I see eighth notes and crescendoes and an andante tempo marking.” After having taken his class I’ll always look through scores that way. It’s so much more helpful than it seems to simply give yourself a few minutes to take in all of the markings on the page because there are often a bunch. And if you’re playing a full musical you need to do that for every single piece of music. That’s a lot of music. So give yourself a few minutes each time to simply look through the music and take in all of the markings.

5. Read lines

When learning to read music we’re often taught to identify single notes. Every Good Barnacle Doesn’t Fall. All Cows Eat Grass. Good Burritos Don’t Fall Apart. FACE. You learn the spaces and the lines as individual notes. That’s useful when getting started, but when you’re reading music you aren’t reading individual notes. You’re reading lines. You’re reading phrases and themes and harmonies. The notes aren’t individual anymore. They’re strung together and stacked on top of each other. Practice reading them this way.

Many times when I’m sight reading I try to look at the ‘line’ that I’m playing as a single line. The notes might be E F# G A B C D, but I’m not really looking at them as an individual E, an individual F#, an individual G, an individual A and so on. I’m looking at it as a scalar run up an E minor scale or G major scale or whatever mode is being used. I’m looking at it as a group of notes. Sure I also realize what notes they are individually, but I’m looking at the line as a whole.

If you have all white notes ascending, try to read them as that. Rather than thinking about individual notes, try to view them as a group.

It’s similar to reading aloud in many ways, though I do realize the “music as language” analogy is quite a tired analogy. When reading aloud we don’t read single words pausing after each word as if they aren’t related to each other. That doesn’t sound natural. We read sentences and phrases that are strung together. That should be the goal with music too. Read phrases and add the appropriate inflections and pauses when playing them.

6. Get better at recognizing chords

This one is simple. Learn a ton of chords and make sure you can recognize the notes in them quickly. This goes back to recognizing patterns.

Be able to notice that the next chord is a C#o7 chord or whatever chord it is. There’s a ton of chords to recognize so I’d start with all of the major and minor chords first. Then move on to diminished and augmented chords. Then look at 7th chords. This one specific step may take quite a while to get down quickly. But that’s fine. You don’t have to do it all at once and if you try you likely won’t improve as much. So focus on the basics first, then add the next few chords when you can.

You’ll also improve your chord recognition abilities the more you read music, so give yourself a break and don’t try to learn every chord in a day.

7. Get better at recognizing scales

This one is also pretty simple and straightforward. Learn all of the major and minor scales. Learn to recognize the key signatures as well as each individual scale written out. Be able to recognize them being played in 3rds or 4ths or some other pattern.

Learn what the chromatic scale looks like. That one can be really helpful if you play romantic music, especially by Chopin, on piano.

Learn the octatonic or symmetrical diminished scale.

Learn the whole tone scale.

Learn all of the modes.

Many of these scales are related so as you learn more you’ll be able to learn them more quickly, but knowing those patterns before reading a piece of music will prepare you for whatever that piece includes.

Quick personal anecdote about this. At Berklee we were studying a piano sonata by Mozart and one of the students was sight reading it on piano. He stopped briefly at a bar long scalar pattern and said something aloud that sounded like, “Oh! Is that? Oh yeah it is”, and then played the whole bar perfectly. Clearly he stopped to recognize the pattern of the notes and once he figured out the pattern and the scale he knew exactly what to play. He was doing this step super quickly. It was an amazing thing to see that happen in real time because it goes to show how much this step can help you sight read music.

8. Get better at recognizing rhythms

Rhythm is something that often tricks people up while sight reading. And it can really throw a wrench in you’re sight reading if you don’t recognize a rhythm. I’ve got a YouTube video on rhythms that would be useful to check out.

Learn the different combinations of rhythms including all different types of rhythms. Learn all the combinations of quarter notes and quarter note rests. Learn the different combinations of eighth notes and eighth note rests as well as combinations of all of the above; quarter notes, quarter note rests, eighth notes, and eighth note rests. Same thing with 16th notes.

This can also be quite a lot so take it slowly. It’s also something that you’ll likely just get better at the more you play and perform and sight read music.

But something you can do is learn the rhythms that are difficult for you. If there’s one type of rhythm that always gives you trouble then practice it a little bit more. Take a look through the piece and make a mental note of which rhythms will give you some trouble. After looking through the piece try to mentally practice the rhythms and “figure them out” before starting to play. This will help you at that measure just a tiny bit so you won’t be surprised. You’ll be prepared for that difficult rhythm.

9. Practice hymns/chorales and theatre music on piano

On piano, one way to improve your sight reading is to practice sight reading hymns or Bach chorales. These pieces can be great practice because they’re very chord heavy. You’ll be reading music in chunks or blocks. Almost every single beat will be a new group of notes to read. They’re also fairly (in a lot of cases) contrapuntal. So you’re practicing some type of contrapuntal playing.

It’ll help you recognize big chunks or chords and notes much faster if you practice a whole lot of these different types of pieces.

Another possible way to practice sight reading is to practice sight reading musicals or theatre music. Opera scores can also be useful. They use a lot of different techniques and have a lot of variation in the music. Some of the playing might also be more related to other piano music, unlike hymns and chorales which are one specific texture throughout.

I personally think both are incredibly useful and should be practiced together to become a more well rounded player. You’re also exposing yourself to a whole lot of different styles of music, which will better prepare you to be able to read whatever music you encounter.

10. Practice Real Book tunes on guitar

For guitar, I’ve practiced songs from the Real Book because they allow you to practice chordal reading as well as staffed reading. It’s great if you’re working on jazz because those are two of the main things you’d need to be able to do when performing. It does leave out more rhythm guitar style stuff that you’d encounter in rock and pop music though, which could easily be added in by reading the chords as if it were a pop song. It might sound a little strange to do this with some standards, but the idea is to practice the reading and technique so whether or not it sounds appropriate for the song doesn’t matter as much.

Another idea for guitar music could be piano-vocal scores or piano-conductor scores where you read the vocal melody and the chords separately. That way you’d likely be practicing the rhythm style of playing that you’d likely see in other styles of music and the lead style of playing you’d likely see in other styles of music as well.

Basically, if you practice sight reading pieces of music within one specific genre you’re more likely to get better at sight reading pieces in that specific genre. It might transfer over to other genres if they share musical characteristics and techniques, but they might not if they don’t share those qualities.

Final notes

The key to getting better at sight reading, on any instrument, is to sight read and play a lot of music. There are specific things to do and learn that will help make that process a little faster and a little easier, but the main thing that you can do to improve your sight reading is to read a ton of music. You need to get the patterns of the music and the patterns of playing that instruemnt under your fingers and so internalized that they’re almost immediate. If you can achieve that goal then you’ll be a much better sight reader.

Good luck sight reading.

ISJ

…

July 9, 2021

Published by admin

I’m working on a new electric symphony (no title for it yet other than that) and I’m basically going through the same process as I did when writing Expanding (An Electric Symphony).

I wrote a few themes, gather my materials and thought of a whole bunch of variations of those themes, created my synths, planned out my movements and then started writing.

The second movement is halfway done right now, and I’m finishing up creating the audio track for the first movement.

I haven’t been specifically focusing on it since writing Expanding, but I’ve improved my music production skills drastically.

So much so that I was incredibly surprised by how good the first movement sounded on the first version of the audio. I’m not using that first version, but I was still incredibly surprised because my music production skills have improved so much.

And I don’t bring this up to brag (though honestly I am incredibly proud of myself), but to make the point that incremental progress in the moment doesn’t feel like anything. But incremental progress over the course of four years can really add up to a lot of improvement. Even if you just improve a tiny bit in a week or a month, after four years you’ll have improved that times 208 weeks or times 48 months.

Regardless of what it is you’ll have improved quite a lot because each of those tiny little steps adds up.

ISJ

…