How to write a pedal (Video)

October 2, 2021ISJ

…

ISJ

…

Being objective about your own playing is incredibly difficult, and it’s harder to do in the moment. Being able to accurately assess your own playing as you are in the middle of playing is one of the hardest skills that musicians have to learn.

But regardless of how hard it is, some amount of self assessment is necessary to improve.

So how do we learn it?

Here are three things that we can do to learn this skill.

The first thing is to play pieces that are below your ability and pay attention to how well you are playing.

The pieces should be fairly easy. Pieces that you can play well work. You want to be able to focus on how well you are playing, rather than focusing on how to play the piece. You want to be able to listen to yourself play the piece.

So choose a piece that you learned about a year ago; one that is easy. As you play it pay close attention to how you are playing each note and how you are articulating each and every part of the music. How are you playing the staccato notes? How are you playing the legato sections? Could they be more staccato or more legato? How quietly are you playing the quiet sections and how loudly are you playing the loud sections? Could you be using a larger dynamic range?

Pay close attention to each and every detail as you play.

The reason you want to use an easier piece is because you want to be able to focus in on how you are playing the music, rather than focusing on the act of playing. You want to be able to easily get your fingers around the notes, rather than having to think about where your fingers are going. You want to have some free attention, almost like you can let your fingers go on auto-pilot as you play so you can focus on the articulations.

Another thing you can do is to record yourself.

Record yourself playing and assess the recordings. It’s not exactly the same because you aren’t assessing your playing in the moment, but it will give you an idea of how you sound and will help you better assess your progress. You’ll be able to listen repeatedly through the recording and assess how you are articulating and playing everything.

After you’ve assessed a recording, practice playing it with the articulations differently, and record yourself again. You’ll want to check your playing a few times to make sure you are able to change how you are playing everything.

If this is a technique you’ve never used then this can be eye opening into how you are playing everything. You might notice that some sections sound much better than you thought they sounded and other sections could be improved because you aren’t able to pay close attention to your own playing as you are playing.

I highly recommend everyone try this at some point in their musical development because it can be such an eye opening experience to be able to hear yourself without having to play.

If you do this though, I do recommend taking into account the way in which you are recording yourself. If you don’t have a proper microphone, or recording space, and the recording conditions aren’t ideal, realize that it likely won’t sound like it was recorded in a studio regardless of how well you play. This won’t affect your playing, but it can affect how “well” and how “professional” the recording sounds.

It’s not a huge deal, but it’s worth mentioning because sometimes when recording yourself for practice it won’t sound like a professional recording. That’s okay as long as you the listener and the player realize it.

One last thing that you can do is compare your own recordings, of your own playing, to recordings of the original players.

If you’re a beginner this tip won’t be useful because recordings of professional players will be quite far above your level. But if you’re an intermediate or advanced player this can help a lot. Try to mimic their playing as closely as you can.

Play their articulations exactly as they play them. Try to mimic how they play every single note and every single articulation. The goal is to be able to sound just like them. Almost like you’re preparing a musical impression of someone. You want to be able to pretend to be that player.

When you play things yourself you can forget all of this, but in doing this you’ll work on articulating things in a new and probably less familiar way than you normally articulate things. Whenever I do this I notice how much more other players articulate things. Some players have a specific way of playing every single note that they play basically.

For example, on guitar a lot of blues and fusion players have some type of articulation on every note. Every note is played with either a slide, a bend, a palm mute, a ghost note hammer-on or pull-off, or a reverse slide. Doing all of those things can be difficult if you’re not used to it. It can be a lot of work to add an articulation to every single note, but in trying to mimic some of your favorite players you’ll get much better at doing it.

Give this a try.

In doing this you’ll get to know your own playing style and how you like to play your instrument. You’ll also learn what techniques are difficult for you to play and what techniques are easy to play.

ISJ

…

Guitar and ukulele. They’re not the same instrument and they sound quite different and have different genres associated with them. But they’re very similar instruments.

They have strings.

They have frets.

They have a bridge and tuners and a head stock.

The strings are even made of the same material for some guitars; nylon.

They play chords and you strum them.

Learning the two of them isn’t like learning two completely different instruments. It’s like learning one instrument and then it’s relative or it’s sibling.

It’s why a lot of string and wind players will play many instruments or double. Once you learn the technique for one it’s not that difficult to learn the technique for another similar instrument.

ISJ

…

Start from the beginning and look through the whole book like a magazine. This might take a while, but make sure you look through the whole thing in one sitting at least once.

Notice everything you can about the music. Notice the keys and generally how the songs are. Notice the tempos and time signatures.

Make a mental note of whether it’s an upbeat song or a slow ballad. Whether it’s a solo number or an ensemble number.

Make notes of what songs will be easy to play and what songs will take some practice.

If there are any songs that you’ll be able to sight read, then you likely don’t need to practice them as much as the more difficult songs.

Once you’ve done a broad overview then start learning the songs. This will likely be the most time consuming part but keep learning them until you’ve gone through all of the songs.

After learning all of the songs, look through the whole book like a magazine again. This will help you to look at the show as a whole and imagine the entire show in your head so you have an idea of the flow of the whole show.

It might not be difficult, but it will be time consuming.

ISJ

…

While practicing we often want to start from the beginning of the piece of music. Almost always. This might feel great, but it’s not all that efficient in terms of practice time.

If we always start from the beginning and re-start every time we make a mistake we end up practicing the beginning section a lot, while not practicing the other music as much.

Let’s look at an example. We’re learning a new piece of music and start from the beginning and play until the 4th measure. In that measure we make a mistake so we re-start the piece of music over from the beginning and play until the 5th measure. We make a mistake in the 5th measure so we start it over again. Then we play until the middle of the 5th measure and we make a mistake so we start over again. We play until the 6th measure and make a mistake and start over again. We do this a few more times making the same mistakes in the 5th and 6th measures.

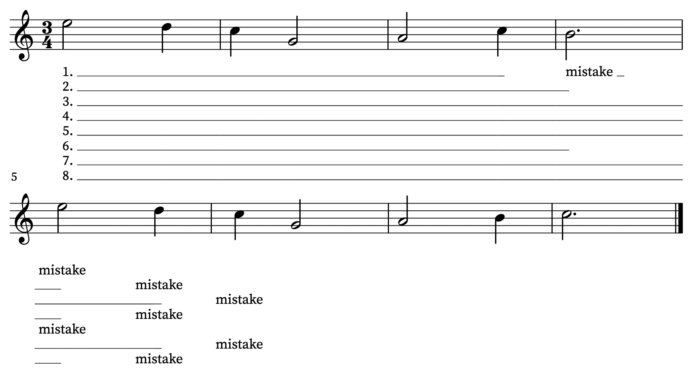

This is illustrated in the picture below where each run through the piece of music is notated by the number at the beginning. The line goes until the place we made a mistake.

Notice how we’ve played through the first four measure the most, but we’ve hardly played through the second half of the melody at all.

This is a short example, but if we imagine this as an expanded, larger, practice session it can easily become a problem. This happens especially when we encounter one difficult section or measure or few beats of music that’s always difficult. We practice up until that section, make the same mistake, start over, practice until that difficult passage, and make the same mistake over and over.

We practice the beginning a lot and get really good at playing the first sections of music. And we hardly practice the sections after the difficult passage.

The solution I’ve found to be the most useful is to separate the music into sections and start playing at multiple different places. Basically, don’t always start from the beginning. This is difficult to do at first because we’ve likely played through the piece starting from the beginning the most and we only know how to play the middle if we’ve played the music before it. It can also be difficult because we can play the beginning the best and that’s what makes us feel good and that’s what’s the most fun to play.

But if we start from different points we end up with a different result in terms of practicing.

In this example we made the same number of mistakes within the first four measures, but because we stopped at the fifth measure and started playing from the beginning again we didn’t make the same mistakes over and over in the 5th measure.

If we continue this throughout the whole piece of music we’ll likely cut our practice time down drastically and learn the piece in much less time than if we used the previous practice method.

When using this practice method you might need to practice transitions between sections in order to play everything in order from start to finish.

Luckily you can use this same mentality for them.

Play just the transition.

Play the measure before and the measure after, but not much more than that. This gives yourself time to get the transition between the sections under your fingers without having to practice a lot of extra music to do so.

If you can play a transition just fine then there’s no need to practice it.

Another consideration is to practice only what you need to. If you can play something well, even if it’s a whole section, then you already know it and don’t need to practice it.

I also recommend adding play-throughs to your practice time. Take breaks periodically to play the whole piece from the beginning. This is the fun part to me because I’m actually playing the music and I get to be expressive, but I think of them as a separate thing from practicing because I’m not trying to get better at any specific material. I’m just playing through it as best I can at the moment.

It’s also a great way to give yourself a break from playing the same few measures over and over and over again. You’ll play different music, give your hands and head a rest for a little so that you can enjoy the piece you just learned.

Give this a try if you struggle with learning music quickly and struggle with the same mistakes.

ISJ

…

Starting from scratch is often difficult. You don’t have any reference or prior knowledge for anything. Things are hard to remember because you don’t have a way to hold onto them.

But you’re rarely ever starting from scratch.

A lot of things are related.

Definitely within on field things are related, but even outside of within one field.

Ideas in music are related to ideas in philosophy and visual art. Many things in music theory are related to math.

Ideas in writing composition are related to ideas in music composition.

You’re rarely starting purely from scratch.

ISJ

…

I’ve been learning flute, clarinet, and violin for about a year now and it’s been going fairly well. I definitely don’t sound great on all of them, but I can play a few songs on each and they sound okay.

That might sound difficult to do, but remember that they aren’t my first instruments and that I’m an adult.

When learning an instrument for the first time you’re working on a number of different skills. Some are related to the instrument itself and some are related to music in general.

You have to learn the technique of that instrument. In learning that technique you’re probably also working on finger dexterity and finger mobility. If you’re learning an instrument as a child that finger dexterity and mobility is just developing. As an adult you’ll likely have more developed finger mobility and finger dexterity. Also remember that finger mobility and dexterity isn’t specific to one instrument. All of the instruments above require learning finger mobility and dexterity.

You have to learn how to play certain notes. That might be learning fingerings on some instruments. That might be learning where to put your fingers on a string. But in learning where to play specific notes you’re also working on what those notes sound like, which is ear training, and you’re working on reading sheet music, if you’re working on reading sheet music. You’re learning about notes and note names and what notes are often grouped together and played in a specific order. Those second two things, ear training and reading music, aren’t specific to one instrument. Those skills are involved in learning all of the above instruments as well.

When learning a new instrument remember that you aren’t starting from scratch every time. If you already play an instrument chances are you’ve already started working on some of these skills that are universal to playing music in general.

Use that knowledge to help you learn the instrument.

Use your ear training knowledge to help you. Use your knowledge of music reading and scales and chords to help you.

Use whatever prior knowledge you have because it can greatly lessen the amount of time it takes to learn an instrument.

For example when I first started learning clarinet I learned the first five notes of a major scale and could already play a few songs with that because I knew what songs used the first five notes of a major scale for their melodies. It wasn’t from scratch at all because I just needed to learn the playing technique and the fingerings. The ear training and theory knowledge was knowledge that I already had and I could use to expedite the learning process. I’d started learning flute a little bit before that so I could use some knowledge of flute fingerings to guess at fingerings on clarinet. They aren’t the same instrument, but the fingerings are often very similar.

Whatever you’re learning, use your prior knowledge to help. It can help much more than you realize.

ISJ

…

This post will be a short story about a show I played a while ago.

I was music directing an elementary school version of Alice in Wonderland Jr. a while ago. It was one of the first shows I’d ever music directed on piano. I just got a new job at a youth theatre program as one of the music directors and was MDing this show and Grease.

We had a number of weeks for rehearsals and to get everything together and they mostly went smoothly. The music in Alice in Wonderland Jr. was a little difficult for me to play on the piano so I had to practice a good bit and simplify some of the sections to make them easier for me to play. But other than that there weren’t a whole lot of problems.

During rehearsals we went through the lyrics for all of the songs and how to sing them and it mostly went well, though some of the students had trouble remembering some of the lyrics.

There were two songs that always gave the students trouble. The songs were “A Very Merry Unbirthday (To You)” and “A Very Merry Unbirthday (To You) Reprise.” They were close in form and in musical content so the students often got them mixed up. Sometimes when singing one song they’d get confused and start singing the other song.

This happened during the performance.

In the middle of one of our performances they started singing the first song, “A Very Merry Unbirthday (To You)” and halfway through they skipped to the middle of the other version, “A Very Merry Unbirthday (To You) Reprise”, and then skipped BACK to the original song, “A Very Merry Unbirthday (To You).”

Luckily I knew the music well and followed them through all of this on piano creating an impromptu arrangement of both songs together. I didn’t turn any pages and just started playing from memory because there was no way I’d be able to find the correct page at the end of the show. I was able to do it all from memory. Luckily the songs were similar and had similar piano parts, but they were in different keys so I had to transpose some of the reprise to the original key. I also had to follow them through the rest of the song because after they skipped to the reprise I wasn’t sure if they would sing the ending of the reprise or the ending of the original.

I impressed myself honestly.

And the director and assistant director of the show noticed this too. They came up to me after the performance and told me, “Good job on following them all over the place during ‘A Very Merry Unbirthday.'”

The reason I mention all of this isn’t just to brag, though it did feel good to be able to do that. It’s to emphasize how important it is to know the music as well as you can. Know the music so well you could imagine it and play it backwards. Know the music so well that you know when someone is accidentally singing the second verse of the reprise rather than the second verse of the original song. Know it so well that you could make a new arrangement of both pieces on the spot.

It doesn’t have to be a perfect arrangement, my impromptu arrangement definitely wasn’t perfect, but the fact that I could make one is the point I’m trying to make. Knowing the music well and paying attention while you’re playing so that you can change the arrangement on the spot if you need to is incredibly important.

And there will be situations in which you’ll be happy you know the music well.

ISJ

…

I always ask my students this question before they play any piece of music. I find that when I ask myself this question about a new piece of music I can learn it a little more quickly.

Knowing when a section is a repetition of previous musical material or when a new section is coming up can be very useful when sight reading or learning a piece of music.

You’re looking at the form of the music. How many sections are there and how many of those sections are repetitions of other sections. Maybe the form of the piece is ABABCAA. In that form you’re playing the A section four times, the B section twice, and the C section only once.

If you’re sight reading and you notice this, you’ll likely play it a little more smoothly because you’ll know that the A section is a repetition and it will be more familiar. The B section is also a repetition and hopefully will be more familiar when you play it the second time.

That last A section will likely sound the best because you’ll be reading through that material for the fourth time, basically like you’ve practiced reading through it three times already.

ISJ

…

One thing that can help you get into composing music and writing music is to start writing antecedent and consequent phrases.

This idea is used a lot in older styles of classical music, but can still be heard in some modern music.

It can also be useful as a type of template to follow to get yourself started.

Antecedent and consequent phrases are two phrases of music, usually around 4 measures each, that start in the same way, but end in two different ways.

For example the first two measures of each phrase would be exactly the same, but the second two measures would differ. Usually the antecedent phrase, the first phrase, has a weaker resolution than the second phrase, the consequent phrase.

Below is an example that I wrote for this post:

Notice how the first two measures of each line is exactly the same. The second two measures are what’s different. The first four measures are the antecedent phrase and the second four measures are the consequent phrase.

Notice also that the first phrase, the first four measures, ends on a B, which is the seventh degree of the C major scale. This would be a half cadence, where the music hands on the dominant chord.

The second phrase, the last four measures, ends on a C, which is the tonic of the scale. Right before that is the note B, which makes a perfect authentic cadence, where the chords resolve from the dominant to the tonic with the melody ending on the root note of the scale.

Using this formula can be really useful when first starting to compose because it gives you a structure to fill in. It gives you a starting place to work with. It also lessens the amount of music you need to write because once you have the first four measures, you really have 6 measures because of the repeated material, and all you need to do is change the ending of the first phrase to make it sound more resolved.

ISJ

…