Thoughts on conducting middle school orchestras

December 8, 2021Full disclaimer before getting into this article I’m in my 4th year as a middle school orchestra director and I direct four groups ranging from beginners to fairly advanced middle school students. I’ve also directed musicals for 4 years.

This article is just my thoughts from having worked with that group of students.

With that out of the way, here are some tips that I’ve found useful to remember in having conducted middle schoolers. Because you can’t conduct them like you would a professional level, or even college level, orchestra. You need to conduct them as middle schoolers. They’ll need different things from you. Here’s what I’ve noticed:

- Be clear

- Know what you want

- Tell them when they play well

- Give them practice time

- Don’t get caught up on small details

- Focus on the big picture

- Choose relevant pieces

- Choose pieces at the appropriate level

- Explain your own conducting

- Don’t take it too seriously

1. Be clear

I mean this both with the gestures that you use and with the verbal directions that you give. If your beat isn’t super clear in your conducting pattern, the students will be off beat. Given the level they’re playing at they likely won’t be able to be super independent with their rhythm and they likely won’t have consistent tempo. So give them a clear beat. Even if the piece is legato it helps them know exactly where the beat is.

Conducting small doesn’t help a whole lot either because they can lose where the beat is.

So regardless of what’s happening in the music conduct fairly big and with a clear beat. It might be a little larger than you’d like for piano and it might be a little too staccato for legato, but it’ll help the players a lot. In general making sure your movements are large can be helpful. Make each movement larger than you would with a professional orchestra.

Something that is useful to remember is that following a conductor is also a skill. Professional orchestra players are really good at following a conductor’s gestures, but middle school players won’t be as good at following a conductor. They’ll also likely be thinking about a lot of different things in the music and with their own playing. So they’ll be trying to focus on a bunch of different things and following the conductor’s gestures is only one of them.

Also when you give verbal directions make sure they’re clear. Say exactly what you want them to do. If they’re sharp tell them they’re sharp. This helps with all conducting but especially with middle school players.

If you hear a wrong note, tell them what the correct note is. If you can, tell them the correct fingering for that note. Though they can always pull out a fingering chart or fiddle with the instrument and find it out themselves, it can save time by giving it to them then and there.

And if you’re not sure what the problem is let them know that as well. No one wants to play for a conductor that refuses to admit any mistakes and pretends that they know everything. An easy way to do this can be simply to say, “I’m not sure what was going on in that section. Let’s try it again so we can figure out what happened.”

2. Know what you want

This one goes with the above tip and it goes with conducting in general. It’s definitely still true for youth orchestras. Know what you want and how you want them to play something.

It helps you conduct more clearly and give more clear directions during rehearsal. It also helps you mentally prepare for the rehearsals if you create a plan of things that you want to work on.

Maybe one rehearsal you practice dynamics. Maybe another rehearsal you practice articulations. Maybe the first rehearsal is just playing through the entire piece to get a feel for the whole thing.

But having a plan of what you want to do and how you want them to play the piece helps create a better performance. It’ll create a sense that the orchestra is one whole, rather than sounding like individual and separate players. They’ll sound more together.

For a lot of this you’ll be telling the players to exaggerate everything. I’ve found that to be the case for dynamics and articulations. I’m always telling my players to play louder for forte sections and quieter for piano sections. You may end up doing something similar with your ensemble, but knowing how you want the performance to sound helps you know which direction to go.

3. Tell them when they play well

I think this one is useful no matter who you’re directing, but I think it applies a little bit more for youth orchestras. The players won’t have the same self awareness that adult musicians have. Adult musicians will likely know when they play something well and when they don’t, even if they aren’t that experienced as musicians. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t tell them when they do play well, but they’ll be more aware of it themselves.

Younger players won’t have that. They’ve heard less music than a lot of adults. They’ve played less music and they’ve likely seen fewer live performances than a lot of adults. So as the director, telling them when they’re doing well can help a lot. It can help them develop that sense of self awareness of they’re own playing and get an idea of what sounds good and what doesn’t sound good.

It’ll also help develop the relationship between you, the director, and the musicians. If they trust that you know what you’re doing and that you’re paying attention to what they’re playing, they’ll follow you more closely.

Lastly, it feels good. This might sound strange as rehearsal advice, but if you’ve been to enough rehearsals, you’ve been through rehearsals that are tense and rehearsals that are more relaxed. Being in a rehearsal with someone that’s not nice to players, is rough for everyone. No one enjoys it, most of all the players. So making sure that the players feel good about their playing can help them play even better.

We’ll talk more about this in #9.

4. Give them practice time

While my youth orchestra was working on an arrangement of “La Vie en Rose” there was a flute solo and a saxophone solo. Those two players could play it well. I’d heard them play it well. Sometimes in rehearsal they would mess up the first few notes or in the middle. I knew they could play it so I didn’t make a big deal and just told everyone we’d try it again. The next time we did it they played it well. I’ve been working with these players for a few years so I knew that they tend to get nervous playing things for the first time in the first run through of the day.

Sometimes giving them a tiny bit of practice time in the rehearsal is all they need. They may just need a refresher on the music and need to play it through once before they can play it well.

Remember they’re middle school players and likely won’t have the self awareness, and experience, to think about looking through the music and playing it through in their head before they play it in rehearsal for the first time. They’ll often show up, put their instruments together, get them out and ready, and start playing without warming up first. Even professional players won’t sound as good as they possibly can if they played like that. That’s why professionals warm up, practice through some parts of the piece, and then they start playing. Professionals know to prepare. Middle school students likely don’t.

So as the conductor you can build that into your rehearsal. Have them warm up a little bit, and practice through the piece a little bit before you start working on it and rehearsing it.

5. Don’t get caught up on small details

Small details like intonation won’t ever be perfect with younger musicians. The same can be said with true dynamic differences or proper articulations. Rhythms also likely won’t be incredibly together. This doesn’t mean that you should ignore things like intonation, dynamics, and rhythms completely, but be realistic about how well they’ll be able to play them.

Some rhythms will likely be played fairly sloppily. That’s fine. The intonation won’t be perfect. That’s also fine. Differences in dynamics and articulations likely won’t be as drastic as you’d like, but that’s okay. Going over small details and spending a lot of rehearsal time on that won’t benefit the players as much as it feels like it will. Things like accurate intonation and rhythms are something that take a long time to develop. They also take a lot of dedicated, individual practice. Practicing them in an orchestra rehearsal likely won’t be the thing that helps them develop those skills.

Intonation is a big one to mention on it’s own here. Intonation won’t be perfect with middle school players. This is for a few reasons, but the main ones are they don’t have the technical ability to play with good intonation and they often don’t have the ear training skills to be able to tell that they’re playing out of tune. They’ll likely be able to hear the fact that they aren’t playing like a professional player, but they likely won’t know specifically what is causing them to sound that way. Even if they have the self awareness to be able to hear that they’re playing out of tune it’s another level of self awareness to be able to tell which way they are out of tune (sharp or flat).

Having that level of self awareness about your own playing, and being able to adjust while your playing is a difficult skill to acquire. And it takes a lot of time; often time that middle school students have not spent on their own playing. It can be useful to review recordings of their own playing, but that would require that your orchestra has a performance first.

One thing I’ve found useful with young singers is having them practice hearing the music in their head first. I’ve done this with students as young as 7 years old and it almost always helps them sing better. I know this article is about orchestra players, but if you’re working with young singers having them practice hearing parts of the music in their head can help a lot. It can even just be a short five minute part of your rehearsals.

6. Focus on the big picture

This one goes with the above tip. Focus on the big picture. Focus on playing the correct notes, somewhat in tune, playing the correct rhythms, playing with some dynamic differences, and playing differences in articulations. Get the general idea of the piece. Playing everything perfectly should not be the goal. And having that goal with younger players can backfire on them. They can get too focused on playing everything perfectly to the point where they hardly play anything at all.

They need to focus on playing a lot and improving their playing. Playing the music as best as they can right now, and then moving on and learning a new piece of music.

Learning to play as an orchestra is another useful skill to teach at this time. Younger players can play with tunnel vision a little bit. They’re so focused on their own playing that they aren’t able to listen to other members of the orchestra. When playing in an ensemble that’s an essential skill, and for younger players having that skill can help them feel more comfortable and confident in their own playing because they’ll know how what they’re playing relates to the other instruments. It can also be helpful in learning your cues. If the music doesn’t have written in cues then it can be helpful to listen to the other instruments to know when you’re supposed to come in. Then you’ll know when to look for a cue from the conductor and will help create a better sound.

Teaching this can come in many different forms because it can be pointing out different parts of the music when rehearsing individual sections. It can also mean choosing pieces that are on the easier side for your players so that they have some extra energy to devote to listening to the piece.

I’m a fan of pointing out what the cues are in rehearsal because I think ear training is incredibly important. So when I tell my orchestra students the cue I’ll be giving them, I also point out what comes before that cue in the music. And it’s helped to try and find something that’s distinct and easy to recognize in the music. Choose a trumpet solo or a saxophone solo or a flute solo if that’s available. Some distinct line that’ll be hard to miss.

Another big picture thing to focus on is the feel or groove of the piece. If a section is legato, focus on having the players play that section somewhat legato, and keeping it more legato than the sections that aren’t legato. Focus on contrasting sections. If one section is rhythmic and staccato and another section is legato, focus on keeping a distinction between the two. They don’t need to playing perfectly legato or perfectly staccato, and bouncing their bows on every note, but the goal should be to hear those two sections as being distinct.

The same can be said for dynamics. If two sections are piano and forte, focus on having them play those two sections at different dynamic levels; loud and soft. As long as there’s a distinction between the two that goal has been achieved. One way to get younger players to do this, that I’ve found to be helpful, is telling them to exaggerate the dynamics as much as possible. Play the piano sections as quiet as possible and the forte sections as loud as possible. That has gotten them to play piano and forte quite well.

A lot of this stuff can be done by telling them, but giving them a cue while conducting is also important for these players. Crouch down when playing piano sections and stand up tall and conduct with a larger pattern when playing forte sections.

Staccato and legato can be a little difficult because conducting with a legato pattern for younger players can cause them to loosen their rhythm and play less accurately. But you can use your left hand to give them a cue for legato or staccato.

7. Choose relevant pieces

This one may be self explanatory, but I’m going to explain it anyways to make sure that I’m being clear. Choose pieces that the students will be able to relate to. It can be useful to choose pieces from the classical orchestral repertoire, but sometimes the players won’t be able to relate to those pieces because they won’t know anything about them. Those pieces will also likely be too difficult for young players to play; even the simpler pieces.

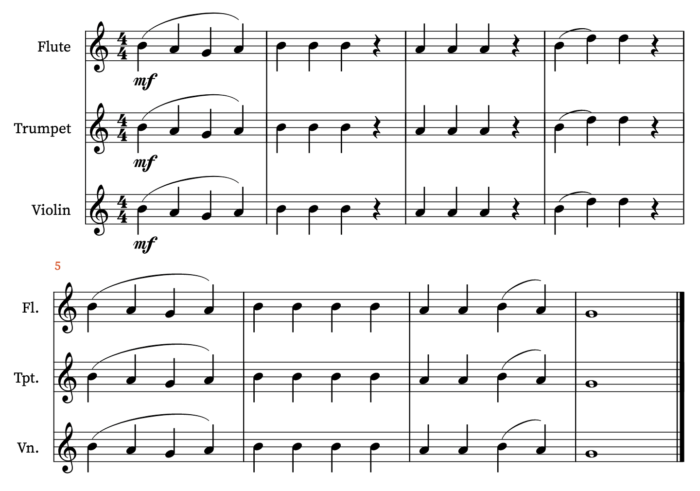

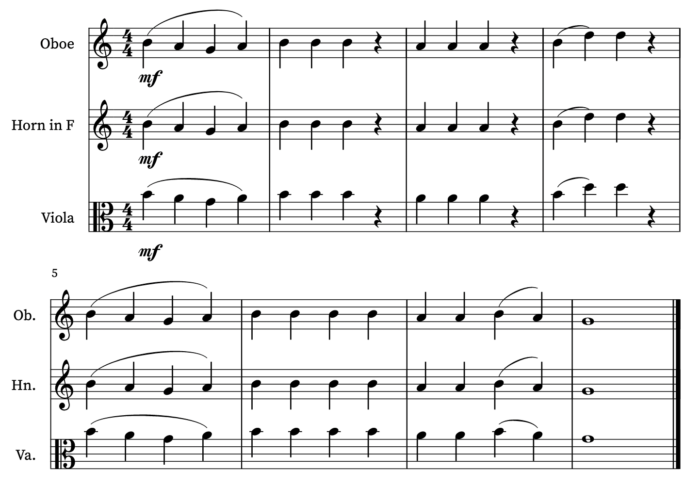

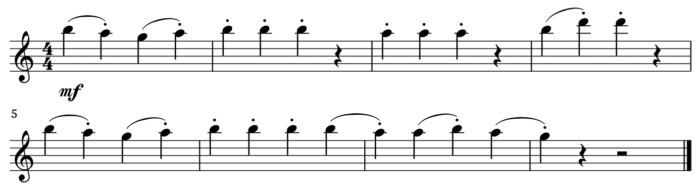

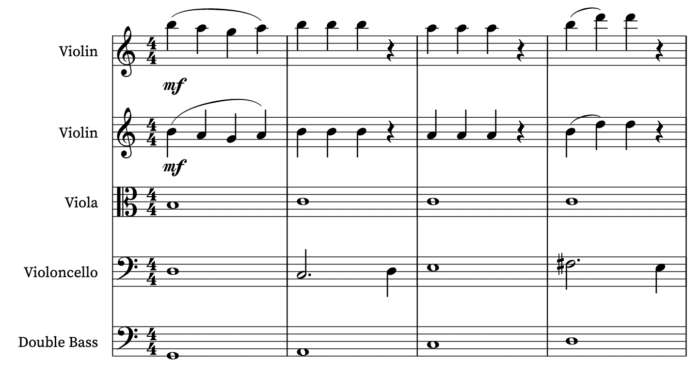

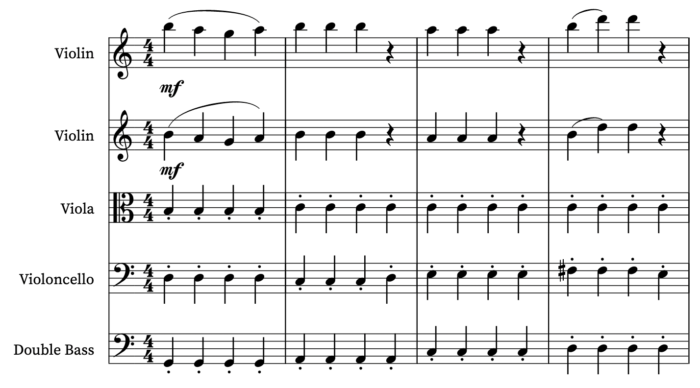

This is time consuming, but I often arrange my own music for my middle school orchestra students because it allows me to choose whatever pieces I want. It also encourages the players because they see that I’m putting in effort to make the music the correct level and relevant to their lives.

Choosing pieces that are relevant may mean choosing arrangements from movies that they likely have seen. It could also mean choosing arrangements of pop songs that they’ve likely heard. It could also just mean choosing the more well known classical orchestral repertoire pieces, though depending on the level of your players, they may be a little too difficult for some ensembles. You may have to find easier arrangements of standard orchestral pieces because they often have runs that are too fast for the violins, notes that are too high for the horns, rhythms that are too difficult, and don’t include saxophone, which is a common instrument to include in middle school orchestras and bands.

Learning to arrange music for your own orchestra can be incredibly useful, but if you can’t do that or that isn’t an option then you can find many easier arrangements online. They often have levels of difficulty listed with each arrangement so you can see whether or not your players will be able to play them. And remember even if the original arrangement doesn’t have an instrument that your ensemble has, you can always give them another similar part to play. For example if the arrangement doesn’t have flutes you could have the flutes play the violin part or the oboe part. As long as the range and key is the same it’ll be fine.

8. Choose pieces at the appropriate level

This one goes with the above tip, but I’ve found that this is one of the hardest things to do. It’s especially hard with a group that you’re new to conducting and gets easier the more you stay with one group. But the main difficulty I’ve found with finding pieces at the appropriate level is a few things. Often younger orchestras have a wide range of technical and music reading abilities. They’re often not all at the same level. They also are often good at specific things, but need to develop other skills that are essential to playing orchestral repertoire. Another thing that makes this difficult is that a lot of orchestral music is not written for middle school players.

If you’re conducting a middle school or even a high school orchestra you’ll likely notice that you have some players that are much better than other players. And with that means that some players aren’t as well practiced as other players. You’ll have a wide range of abilities. Sometimes this might mean that some players could sight read the pieces that you give them, and others may need a few months to practice them. That makes it difficult to keep everyone engaged and enjoying the experience because no matter what pieces you choose some players will get bored easily and others will be struggling a lot.

I’ve noticed with my own players that they have some gaps in their playing abilities. They may be good at reading music, but their technique needs to be developed more. Or the other way around is probably more common. They have great technical abilities, but their music reading skills aren’t up to that same level. Sometimes it may be things that are specific to their previous teachers. Some players may know how to play a lot of accidentals, but others may not. Some players may be able to play quite fast, but they might not be able to read more than four key signatures.

Key signatures and time signatures can be a difficulty for younger players too. Even if they know all of the notes, if it’s a key signature that they’ve haven’t played in that may cause them to play more timidly because they’re unsure of their own abilities. Similarly, accidentals can throw some players off, even if they know how to play those notes. For example seeing an F#, written in a piece in C major, can confuse some players simply because it’s not in the key signature and it seems unfamiliar. The same can be said for F naturals in a piece in D major.

The last thing that just sucks about choosing music is that there aren’t a whole lot of pieces written specifically for middle school players that are well known pieces. There’s quite a good amount of music to choose from, but it’s often music the players won’t know or won’t have heard before. Likely because the pieces have to stay at a limited level, and that limited level may not always be the most exciting music to listen to. Those pieces aren’t played very often if ever by anyone other than middle school orchestras. This isn’t something that can be fixed in a rehearsal because most standard orchestral repertoire is quite far out of the playing ability of younger players. So adjustments need to be made.

I’ve found arranging music to be the best solution because I don’t have a personal music library, but there are plenty of websites to order arrangements from. Below are a few that I’ve found useful:

9. Explain your own conducting

This is something that I do with my orchestra students because I’ve found that it helps them to know what I’m doing. If I’m giving them a specific cue, or a count off, or some other specific movement, I explain what I’m doing and why I’m doing it.

It’s useful to remind yourself that these students haven’t had as much practice following a conductor as older students have had. They aren’t familiar with how conductors handle certain things and they likely aren’t as good at following the conductor and reading their music at the same time.

So it can be useful to explain to them what movements and motions you’ll be giving them so that they’re prepared and know what to look out for.

This can be incredibly useful if you’re giving multiple cues within a short time frame. If you’re cuing two different instruments within a few beats of each other, let each player know which movement is their cue, and make sure that each movement is clear, and let them know which movement isn’t their cue.

They’ll likely know some basic conducting patterns, but they won’t know a whole lot about conducting. If you’re conducting a new pattern or a new time signature, explain to them what the pattern is and where to see each beat. It can be helpful to tell them that the largest preparation beat for them is the last beat of every pattern. Almost every conducting pattern has a very large up stroke at the end of the pattern. The fourth beat in 4/4 is in the center and then a large upwards motion to prepare for the first beat of the measure. The same is true of 5/4, 3/4, 6/8, and basically every conducting pattern.

Just knowing this can be incredibly useful because then they know what to look for for the first beat of the measure; the big upwards motion.

If your music has fermatas or caesuras or anything that would change the conducting pattern, let them know. Explain what you’ll be doing before, during, and after that beat so they’re prepared to follow you.

It can also help to look up from your score and make eye contact with the players. Looking at them and giving them some type of facial cue can also help communicate to them what they’re supposed to be doing.

Remember that these players are young and sometimes young players play with a type of tunnel vision focus on their own music … literally. They’re so focused on playing their own music and thinking about where their fingers should go and how their embouchure should be that they forget to look up and follow the conductor.

Making it easy to follow you can help a lot.

10. Don’t take it too seriously

Remember that they’re still kids. They’re not professionals and they won’t sound like professionals. Don’t take it too seriously. Even if you’re competing. Remember that they’re still kids.

Orchestra rehearsal should be fun and enjoyable. At the very least it shouldn’t be something that the students dread going to.

If you have players that are excited to play in your orchestra and enjoy the experience of playing in your orchestra you’ll have players that sound much better. You’re also setting them up to enjoy music throughout the rest of their life because you’re giving them a good experience with music and orchestral playing.

The players want to sound good just as much as you want them to sound good. So set them up to sound good.

Also let’s be honest. Making a mistake in a middle school orchestra isn’t the end of the world. It’s largely inconsequential in the grand scheme of music and performing. Even if a concert doesn’t go well it’s not the biggest deal in the world. Have some perspective when performing and rehearsing with your students. They’re still students and they’re there to learn.

A tense rehearsal is not the optimal space to make music and definitely isn’t the optimal space to learn.

Final notes

I really enjoy directing my middle school orchestra students. It can be a lot of work, and honestly the pay isn’t great where I’m at right now, but it’s definitely an enjoyable thing for me to do. And the whole experience is made more enjoyable when my students enjoy what they’re doing.

If they’re having a good time then I’m having a good time. But if one of us isn’t having a good time then likely neither of us is having a good time. So try to make sure that while you’re getting your players to play as well as they can, try to get them to also play something that you enjoy directing, and they enjoy playing. It’ll make for a better experience for everyone.

I’ve noticed that me simply choosing pieces I enjoy makes the entire experience easier for them. It gets them excited to see that I’m excited. If I excitedly tell them that they’re playing well, they’ll be excited about it too. They’ll follow your lead a lot of the time.

And finally if you’re conducting a middle school orchestra and would like an arrangement for a piece of music, feel free to contact me and we can discuss rates and delivery specifics. I’ve also got a fair amount of music already arranged if you’d like to see the arrangements I’ve already made.

ISJ

…